Next Steps for Policy and Public Health Research

In a landmark press conference on April 16, 2025, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. delivered a sobering diagnosis—not of a child, but of an entire nation. Flanked by researchers, parents, and reporters, Kennedy declared that the United States is facing a public health crisis of staggering proportions: the autism epidemic. The numbers he cited were not projections or hypothetical models. They were hard, government-issued statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): as of 2022, 1 in 31 American 8-year-olds—more than 3.2%—carry a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a sharp rise from 1 in 36 just two years prior. Among boys, the rate is even more harrowing: 1 in 20 nationally, and in California, where tracking systems are most sophisticated, a staggering 1 in 12.5.

“This is not just a public health issue,” Kennedy stated. “It is a national emergency.”

These numbers are not outliers or isolated spikes. They reflect a long-standing, uninterrupted upward trajectory that began in the early 1990s and has continued through every revision of diagnostic criteria, every public awareness campaign, and every wave of technological advancement in health surveillance. In 2000, the CDC estimated that 1 in 150 children had autism. In the 1970s, the rate was 1 in 10,000. This means the current figure represents more than a 300-fold increase over historical estimates—a climb far too steep to attribute to mere improvements in detection. When challenged by a reporter if he denied that efforts to bring healthcare to “underserved populations” were contributing to the rise in autism cases, Kennedy estimated at least 85% of the increase is real.

And yet, that is precisely the line many public health officials and media outlets continue to promote. In a coordinated media response following the CDC’s 2025 report, major outlets such as The Washington Post, NPR, and The Hill characterized the rise as “slight” and credited the increase to “better screening” or expanded diagnostic definitions. Kennedy forcefully rejected these explanations, calling them “industry canards” designed to deflect attention from a growing body of evidence pointing toward environmental causation.

He’s not alone. Joining him at the press conference was Dr. Walter Zahorodny, lead autism prevalence researcher at Rutgers University and principal investigator for New Jersey’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) site. Zahorodny emphasized that the rise in autism is not a diagnostic illusion: “There is better awareness of autism,” he said, “but better awareness cannot be driving a disability like autism to increase by 300% in 20 years”.

This moment marks a historic inflection point—what public philosophers of science might call an epistemic break. For the first time in modern history, a sitting HHS Secretary is rejecting the dogmatic notion that autism’s explosive rise is an artifact of increased awareness. Instead, Kennedy is calling it what the data clearly show it to be: a genuine epidemic of neurological and immunological injury in children, one that demands immediate, rigorous investigation.

To that end, Kennedy announced that the Department of Health and Human Services, in coordination with the CDC and independent global researchers, has launched a sweeping, agnostic inquiry into the environmental causes of autism. This effort, involving hundreds of scientists, will not be limited to politically safe topics or agency-approved hypotheses. It will include examination of pesticides, food additives, water and air pollution, pharmaceuticals, and—yes—vaccines and their ingredients. “We are going to look at every plausible cause,” Kennedy said, “and we will follow the data wherever it leads.” The initiative promises preliminary results by September 2025.

This declaration is more than symbolic. It represents the potential end of a decades-long pattern in which environmental hypotheses—particularly those implicating iatrogenic exposures such as vaccine adjuvants or medical interventions—have been marginalized, censored, or defunded. Kennedy’s announcement reflects a long-overdue course correction, not only for autism research but for the credibility of public health itself.

At stake is not merely scientific clarity, but a generation of children. The urgency could not be greater. As Kennedy warned, “We are losing our children. And we are doing it to ourselves.”

What follows in this report is a detailed synthesis of Kennedy’s policy pivot and the scientific literature that supports it. This report will dismantle the denialist narratives that have dominated public discourse, replacing them with a rigorous, testable, and biologically coherent framework. Autism is not a mystery. We have not failed to understand it. We have only failed to look where the truth resides.

And now, finally, that is beginning to change.

Autism Prevalence: A Real, Accelerating Epidemic

Despite persistent efforts to reframe autism as a benign neurodivergence or a diagnostic abstraction, the data tell a radically different story—one of exponential growth, expanding disability burden, and increasing severity. The numbers are not merely alarming—they are devastating.

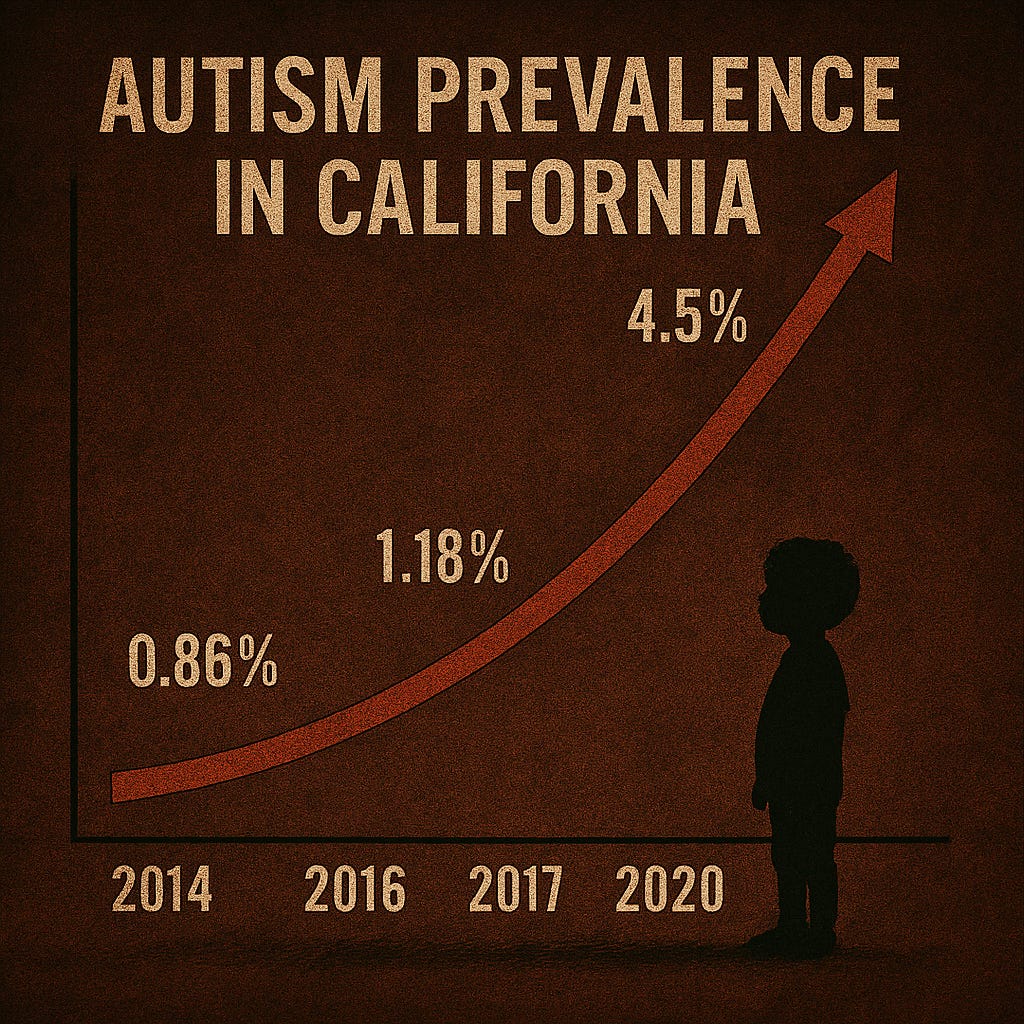

According to the CDC’s 2025 Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network report, the national prevalence of autism among 8-year-olds rose from 1 in 36 in 2020 to 1 in 31 in 2022, representing a 17% increase in just two years. The gender disparity is stark: among boys, the rate is 1 in 20, and in California—widely regarded as having the most rigorous autism surveillance systems—the number is 1 in 12.5. These are not isolated spikes or outlier data points; they are the latest entries in a persistent trendline that has been climbing, unbroken, for decades.

What makes these findings even more consequential is the pattern among younger cohorts. In five of the CDC’s 16 study sites, the autism rate among 4-year-olds already exceeds that of 8-year-olds, strongly suggesting that future reports will show even higher national prevalence as these children age into formal diagnosis. This undermines the assumption that we are merely detecting autism earlier. Rather, it signals that the baseline incidence continues to rise.

The massive scientific literature that existed ten years ago described this trajectory as not merely an increase but a pathological acceleration, one that can no longer be attributed to demographic shifts, diagnostic reclassification, or administrative factors. In my book, The Environmental and Genetic Causes of Autism, I reviewed a huge body of peer-reviewed evidence that systematically dismantles the artifact theory. For example, Nevison (2014) demonstrated that even after adjusting for changes in diagnostic criteria and increased awareness, the dramatic rise in autism diagnoses remains largely unexplained—unless environmental exposures are included in the model.

Moreover, the nature of autism being diagnosed has changed in ways that defy the mainstream narrative. If the increase in prevalence were due primarily to better detection of high-functioning or mild cases, one would expect a concurrent increase in the proportion of children with higher IQs. But the opposite is true. The CDC report shows that nearly two-thirds of children diagnosed in 2022 had IQs below 85, meaning they are cognitively impaired or borderline. This figure has grown over time, not shrunk. These children are not “quirky geniuses” simply being noticed more—they are deeply disabled, often non-verbal, and require lifelong support.

This disproves what Kennedy termed the “epidemic denialism” narrative, repeated ad nauseam by academics and media outlets with deep entanglements in institutions historically resistant to environmental causation. The Washington Post, for example, labeled the 17% increase as “slight”. But as Rutgers’ Dr. Walter Zahorodny, one of the principal investigators in the CDC’s own surveillance network, countered, “Better awareness cannot be driving a disability like autism to increase by 300% in 20 years.”

Existing science goes further, pointing to population-level implausibilities inherent in the artifact argument. If autism rates truly had remained constant over time, as some genetic determinists claim, we would expect to see comparable rates in adults over 35, including millions of severely affected individuals who would require intensive care, group housing, or institutional support. They are simply not there. Kennedy poses the blunt question: “Where are the older adults with profound autism?” The answer is self-evident: they never existed in such numbers, because something changed in the environment in recent decades that did not exist in previous generations.

Kennedy, Zahorodny, and rational scientists converge on the same conclusion: the data are real, the increase is real, and the only scientifically responsible position is to treat the autism surge as a genuine epidemic. The public health implications are catastrophic. As Kennedy noted during the press conference, the rising rates of severe autism are not only devastating families—they are eroding the nation’s future:

“These are children who, many of them, were fully functional and regressed. They will never write a poem, never go out on a date, never live independently. We are doing this to our children, and we have to stop.”

Critics may bristle at the bluntness of this statement, but it reflects a deeper truth: ignoring the magnitude of the crisis in the name of social comfort or political expediency is itself a form of abandonment. It is not Kennedy who is stigmatizing the disabled—it is the mainstream public health establishment that has failed them, by refusing to investigate why the disability is becoming so much more common.

That said, Kennedy might have done well to point out that The Spellers program is revealing an army of previously non-communicative poets, philosophers, scientists and politicians in young adults who suffered the environmental exposures that revealed their genetic susceptibility.

In the next section, we will examine the inadequacy of genetic determinism to explain the autism epidemic and explore why the scientific consensus must shift toward gene-environment interaction as the primary lens of investigation.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel