On October 24, 1861, workers completed construction of the link connecting eastern and western telegraph networks of the nation at Salt Lake City, Utah, completing a transcontinental line that for the first time allowed instantaneous communication between Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, and effectively put an end to the Pony Express.

The idea behind the Pony Express—a horseback relay mail service—goes back to thirteenth-century China, where Marco Polo saw “post stations twenty-five miles apart.” In 1843, Oregon missionary Marcus Whitman proposed using a relay of “fresh horses” to deliver mail from the Missouri to the Columbia in forty days.

In 1845 it took President James K. Polk six months to get a message to California, which dramatically exemplified the need to improve communications in the expanding nation.

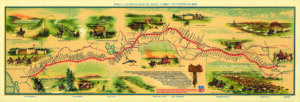

When first placed into operation the Pony Express carried the mail once a week in each direction, east and west. The delivery time of mail from St. Joseph to San Francisco was reduced to 10 days—a revolution of its time. Later trips were made in eight or nine days.

The fastest trip ever made by the Pony Express was when Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. Details of Lincoln’s inaugural address covered the distance between St. Joseph and Sacramento in seven days, 17 hours.

Pony Express riders were hired at $50 per month, plus room and board. Over time this rose to from $100 to $125. A few whose rides were particularly dangerous or who braved unusual dangers received $150.

The prospect of good pay and adventure attracted young men. In St. Joseph and in Sacramento, crowds of young men showed up eager to apply for jobs as riders and hostlers.

The Sacramento Union reported that on April 3, 1860, when riders left San Francisco and St. Joseph simultaneously, crowds cheered.

After the development of efficient telegraph systems in the 1830s their use saw explosive growth in the 1840s. Samuel Morse’s first experimental line between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore – the Baltimore-Washington telegraph line – was demonstrated on May 24, 1844. By 1850 there were lines covering most of the eastern states, and a separate network of lines was soon constructed in the booming economy of California.

California had been admitted to the United States in 1850, the first state on the Pacific coast. Major efforts ensued to integrate California with the other states, including sea and overland mail and passenger service.

The federal contract authorized through the Pacific Telegraph Act of 1860 was awarded to Hiram Sibley the president of the Western Union Company, who then formed a consortium between Western Union and the telegraph companies in California: to share the efforts of constructing the overland telegraph, to split up the federal and state subsidies, and to share any profits from operation of the line.

The newly consolidated Overland Telegraph Company of California would build the line eastward from Carson City (the eastern terminus of their lines) using the newly developed central route though Nevada and Utah.

At the same time the Pacific Telegraph Company of Nebraska was established to construct a line westward from Omaha, essentially using the eastern portion of the Oregon Trail. The lines would meet at a station in Salt Lake City.

It’s difficult to imagine the obstacles to building the line over the sparsely populated and isolated western plains and mountains of the frontier. Wire and glass insulators had to be shipped by sea to San Francisco and carried eastward by horse-drawn wagons over the Sierra Nevada. Supplying the thousands of telegraph poles needed was an equally daunting challenge in the largely treeless plains country, and these too had to be shipped from the western mountains.

Telegraph line workers faced perils and hardships, daily. Weather, working conditions, and the need to complete the job created untold pressures.

Renegade Indians also proved a problem. In the summer of 1861 a party of Sioux warriors cut part of the line that had been completed and took a long section of wire for making bracelets. Later, however, some of the Sioux wearing the telegraph-wire bracelets became sick, and a Sioux medicine man convinced them that the great spirit of the “talking wire” had avenged its desecration. Thereafter, the Sioux left the line alone, and the Western Union was able to connect the East and West Coasts of the nation much earlier than anyone had expected, a full eight years before the transcontinental railroad would be completed.

Although in action for only 19 months, until the completion of the transcontinental telegraph, the Pony Express ceased operations just two days after the last telegraph wires were joined together, and the last of the Pony Express riders’ mail was delivered.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel