In 1948, a World War II-era bomber crashed into Lake Mead, the massive reservoir formed by Hoover Dam that straddles the Arizona-Nevada border. After several failed attempts to locate the plane, it was finally discovered in the early 2000s—still remarkably intact.

In the early 1940’s, the military recognized that the U.S. might be drawn into a global conflict in Europe and perhaps the South Pacific. A call went out from the War Department to develop a new bomber—something that could carry a heavier load and fly greater distances. The president of Boeing responded, and the company started putting designs on the drawing board for the “B-29 Superfortress.”

After the Pearl Harbor attack in December, 1941, Boeing moved ahead with its development of the B-29. Archeologist Jeff Wedding says it would be twice the size of existing bombers, carry double the payload, go twice the distance, and travel 100 miles an hour faster than anything flying at the time. It would also be the first military aircraft to have a pressurized cabin. Crews flying combat missions aboard B-17 and B-24 aircraft wore heavy winter gear and used oxygen at altitude. In the B-29, pilots could fly in shirtsleeves, breathing cabin air like passengers on today’s airliners.

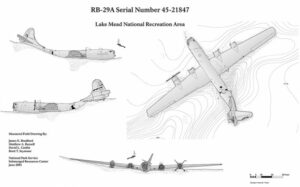

The Lake Mead B-29 rolled off the assembly line 11 days after the Japanese surrender in September 1945, so it never saw combat. It was designed for photo reconnaissance, and to reduce weight and provide space for the cameras, it carried no military hardware.

Dr. Carl Anderson, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) and Nobel Laureate, saw the potential of using B-29s to study cosmic rays submitted a request up the chain in the military to use a B-29, and eventually three planes were assigned to Project APOLLO, the High Altitude Flying Laboratory Program, and were based at Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) InyoKern, now called Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake.

Dr. Carl Anderson, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) and Nobel Laureate, saw the potential of using B-29s to study cosmic rays submitted a request up the chain in the military to use a B-29, and eventually three planes were assigned to Project APOLLO, the High Altitude Flying Laboratory Program, and were based at Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) InyoKern, now called Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake.

After the war, many B-29s were mothballed, but the Lake Mead plane with its observation windows was perfectly suited to do research that had been put on hold during the war years—in particular, research on cosmic rays. Cosmic rays are high-energy particles that originate in deep space and are constantly bombarding the earth.

On July 21,1948, the B-29 bomber crashed into Lake Mead, the massive reservoir formed by Hoover Dam that straddles the Arizona-Nevada border. After several failed attempts to locate the plane, it was finally discovered in the early 2000s—still remarkably intact. As lake levels fall, will the draw to see the aircraft finish it off?

There were a few unsuccessful efforts to locate the plane, including by the co-pilot Hesler, who had hired a salvage diver. Also, park staff at the time went to the Overton Arm area of Lake Mead where the plane went down to look for fuel stains on the water’s surface.

The official crash report said the pilots were flying low to collect a last bit of scientific data before returning to base and that the instruments on their B-29 aircraft were improperly calibrated. Also, the account said that Lake Mead—smooth as glass on that July morning in 1948—distorted their depth perception and sent the plane skipping like a stone across the water.

The official crash report said the pilots were flying low to collect a last bit of scientific data before returning to base and that the instruments on their B-29 aircraft were improperly calibrated. Also, the account said that Lake Mead—smooth as glass on that July morning in 1948—distorted their depth perception and sent the plane skipping like a stone across the water.

There’s another side of the story that’s not in the official record but was part of the lore repeated by the flight crew and the scientist afterward, says Susan Edwards, an archaeologist and historian at the Desert Research Institute or DRI. “The pilots were hotdogging. It’s fun to fly as low as you can. It just is.”

Whatever the truth, when the B-29 (S/N 45–21847) hit Lake Mead, the impact stripped off three of its four engines and took out part of the tail as one of them whipped past. Edwards says the pilot, Captain Robert M. Madison, and the co-pilot, 1st Lieutenant Paul M. Hesler, were able to wrestle the plane back into the air for about another 200-300 yards, but with only one engine left and it on fire, the pilots feathered it and were able to ditch the plane straight and level.

They popped the hatches to escape—four of the five crew members, anyway. Sergeant Frank Rico was in the back of the plane and broke his arm after being thrown against the bulkhead. He was trying to crawl from the rear cabin to the nose of the plane, but his parachute got stuck.

The B-29 was going down tail first. The crew realized that Rico had not surfaced and heard him banging on the interior. Madison, and the scientist aboard that day, John W. Simeroth, went back in and were able to drag Rico through the aircraft and then out emergency windows on the cockpit. They all got into rafts, and the plane went down about 12 minutes later.

The crew hadn’t been required to file a flight plan, so no one from the InyoKern military base in the California desert (now called China Lake) where the flight originated was aware of the accident. The airmen discharged a dye canister, and a TWA pilot, who served in World War II and was flying overhead, recognized the distress signal and reported it.

The men were rescued five hours later by Park Service personnel, but the B-29 would come to rest in a watery catacomb almost 280 feet below the lake’s surface.

It sat undisturbed until 2001, when a local diver, using a side-scan sonar—which without a permit is against park regulations and illegal—located the B-29.

Dave Conlin, chief of the Submerged Resources Center (SRC) of the National Park Service, which manages underwater assets in the park system, recounts that the man and his team started diving on the plane at a depth of 230 feet. Over the course of a year, Conlin says, they set up lights and were filming, and also removed items from the B-29. Their idea was to do a documentary, file a salvage claim under admiralty law, raise the aircraft from the bottom of the lake, and sell it.

Lake Mead National Recreation Area officials only found out about the discovery after one diver’s father held a press conference to announce that the aircraft had been found. They refused to release the coordinates to park staff, so Conlin’s team asked the Bureau of Reclamation for help. The agency conducts surveys to assess how sedimentation is changing the water volume of the lake, and using their high-resolution data, the SRC was able to locate the plane.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel